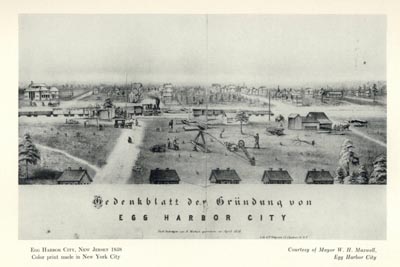

EGG HARBOR CITY:

NEW GERMANY IN NEW JERSEY

By DIETER CUNZ

Egg Harbor City, a charming and pleasantly sedate town of 5,800 inhabitants, inland between Philadelphia and Atlantic City, is neither a city nor a harbor. Remains the egg, for which the Jersey folklore has a quick and ready answer, to us so unconvincing that we have to relegate this information into a footnote. 1

The average tourist who rushes through the town on his way to the New Jersey seashore will probably not notice anything in particular. Perhaps he will make a remark about the exceptionally large number of well kept gardens with beautiful trees and shrubbery. A tourist who has an ear for German sounding names or a college student who ever took a course in German civilization will probably look somewhat perplexed if he opens the local telephone directory or if he sees the names on the street signs. There is Suenderhauf’s Bakery, Weisbecker’s Cleaners, Von Bosse’s Winery, Messinger’s Grocery, Theilacker’s Flower Shop. People live on Hamburg or Bremen Avenues, or on streets named for Beethoven, Buerger, Campe, Claudius, Diesterweg or Duerer.

The explanation for this abundance of Germanic sounding names everywhere in Egg Harbor City would have to be found in the early history of the town, a history of exactly one century, because the Egg Harbor story began in 1855. Here as so often in American history the railroads brought a new political and economic impulse. In the year 1854 a new railroad had been built, the Camden & Atlantic Railroad, connecting the big East coast lines running through Philadelphia with the newly opened seashore resort Atlantic City. 2 A railroad was an all-year-round business. It could not exist exclusively on the summer seashore traffic. Thus the railroad company had a vital interest in filling up the demographic white spots in the thinly settled stretches of land between Philadelphia and the coast. Towns would have to be founded along the line.

On the Board of Directors of the railroad company there were several men of German descent. They may have conceived the idea of a German settlement. However, this alone does not account for the fact that Egg Harbor City was planned as a pure German town and that this project soon became known to German-Americans all over the country. The decade preceding the Civil War was a time of turmoil and unrest, of tension and prejudice. The biggest wave of anti-immigrant resentment in American history, a nativistic movement called Knownothingism, swept the country. Irish and German immigrants became the main targets for this militant and aggressive group. Germans in Baltimore and Buffalo, in Richmond and St. Louis were haunted by the fear of mob violence and persecution. Many German newcomers who had felt the pressure of the Knownothings were in a receptive mood when they read the advertisements inviting them to a purely German settlement in the New World.

It was this combination of two phenomena, both typical of the United States in the midcentury, railroad expansion and anti-immigrant feelings, to which Egg Harbor City owed its existence.

When on July 1, 1854 the first train of the new railroad left Camden and puffed eastward, the official party included a good number of prominent German-Americans from Philadelphia, among them William and Henry Schmoele and Philip Mathias Wolsieffer. 3 On November 24, 1854 they organized in Philadelphia a corporation, the "Gloucester Farm and Town Association." In the midst of the New Jersey woods they bought about 38,000 acres, mostly second-growth pine land, on which a German settlement should rise. 4 The first railroad station for the settlement-to-be was named Cedar Bridge.

In their initial plans the promoters went completely overboard. They visualized two cities, one, called Pomona, stretching over four square miles immediately north of the railroad tracks. A second city, called Gloucester, should be erected a few miles further north around Gloucester Lake. 5 Soon the scheme of twin cities was dropped and the project was considerably reduced to still unmanageable proportions: one great commercial metropolis and harbor should be built on the seven-mile tract between the railroad and the Mullica River and should be named Egg Harbor City.

The Gloucester Farm and Town Association was incorporated on December 14, 1854. The charter of the city bears the date March 16, 1858. 6 The population of Egg Harbor always considered September 1855 the beginning of their history, probably because the first settlers arrived at that time.

The original idea seems to have been to develop simultaneously an urban core and a loosely settled farming area. Stock was issued, the first series at $300 per share, the second at $400. With each share the new settler and stockholder acquired a 20 acre farm and the claim for a building lot 100 by 150 foot within the "town" (in the narrower sense of the word). Settlers who were interested only in the city ground could purchase a city lot for $78.00. The Association added a good number of additional enticing advantages, gifts and promises: trees would be planted along the streets, a park of almost 100 acres would be laid out, schools would be constructed: "in brief, every dollar that we receive will be spent again in the settlement and for the settlement." 7

The far-reaching plans of the promoting Association were revealed in an article by its president, published in the Unabhängige Heimstätte of March 29, 1856. 8 Here, he said, was for the Germans in America the chance to build a flourishing agricultural colony, a great commercial and industrial center and to preserve all the national qualities of the German element in a homogeneous Germanic population. German-Americans, living elsewhere in the United States, might consider a move to the new city. Direct immigration from the German fatherland might be channeled into Egg Harbor to swell the ranks of the settlers.

In 1859 the Association put out a special pamphlet under the heading "Was wir wollen—What we want." The answer developed the entire program of the project. What did they want? "A new German home in America. A refuge for all German countrymen who want to combine and enjoy American freedom with German Gemütlichkeit, sociability and undisturbed happiness. A place to develop German folk life, German arts and sciences, especially music. A place around which we can build German industry and commerce, a practicable harbor and railroad connections to all parts of the country." 9 It was an appeal in hymnic emotional prose which was even turned into rhyme and meter, culminating in the words:

| Hier, geliebte deutsche Brüder, |

| Findet ihr die Heimat wieder. |

These two lines became a sort of a themesong or leitmotif in the advertising campaign and were frequently repeated as a motto at the beginning of advertisements in German-American newspapers.

The Association evidently invested a great deal of money in a vigorous and far-reaching advertising campaign in all American cities with a sizable German population. The waves of propaganda were beamed only to German-Americans or to newly arrived immigrants from German speaking countries. An advertisement in the Baltimore Correspondent in 1858 mentions regular Egg Harbor agents in Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Newark, Buffalo, Cleveland, Baltimore and Washington. 10 Two years later the Association had agents in twenty-nine cities of the United States, as far west as St. Louis and Milwaukee. 11 Egg Harbor in the fifteen years after 1855 was not a local New Jersey affair, but a nationally advertised German-American undertaking, an experiment which the Germans all over the country watched with intense interest.

In January 1858 the Germans of Baltimore were invited to a mass meeting at which Dr. W. Scheible, one of the founders of " this biggest and most beautiful German enterprise in America" informed his fellow Germans about the advantages of Egg Harbor. 12 It is interesting to note that in many of the articles, reports and advertisements the promoters emphasize that the new city would be free of all the disadvantages which compelled many a German to leave his home in the Old World: free of the obsolete and oppressive spirit of class distinctions and free of all social, political and economic restrictions such as prevailed in the atmosphere of the German states. 13 Beyond such generalities the advertisements skillfully took note of special local conditions. Baltimore, for instance, was particularly plagued by the Knownothing fever. 14 Again and again German festivals and meetings were violently disturbed. German immigrants were beaten up or intimidated. It was in these years that the city acquired the name of "Mobtown." An article in the Baltimore Wecker, addressed to the Germans of Baltimore, took this situation into account: "You had courage enough to leave your beloved fatherland, to escape the hands of the tyrants and to search for a new home here. In Baltimore you found all this for only a short time, since during the last years neither your life nor your property has been safe. Are you chained to the soil? Did your former courage evaporate? Do you want to be robbed and killed? No. Leave a city in which you and your children are threatened by misfortune and contempt. Thus I invite all of you who still have some courage to leave this town of robbers and murderers. Come and be informed about a new free home." 15

A perusal of the German newspapers in Baltimore indicates that the German element here took a very strong interest in the Egg Harbor experiment, to such an extent that later the idea arose that the project had originated among the Baltimore Germans. "Egg Harbor is so to speak a daughter of Baltimore," said the Correspondent in later years, "for the colony was founded by Germans of Baltimore." 16

Egg Harbor City had its beginnings in the offices of some wealthy Philadelphia financiers. However, a settlement of human beings does not proceed like a chemical experiment. Too many intangible elements and unpredictable factors enter into the picture. Although the settlement association insisted that all and everything was done for the common good, the settlers took nothing for granted in this respect. In 1860 the "Conservative Männerverein" was founded which wanted to protect the interest of the settlers against the Philadelphia business men. In the spring of the same year the Gloucester Farm and Town Association was fiercely attacked by the settlers on account of its spirit of capitalistic exploitation. Particularly the brothers Henry and William Schmoele were under fire. They were repeatedly accused of having used settlement funds for the promotion of their private schemes. The entire board of directors was severely criticized for not carrying out their promises and for not giving sufficient aid to the settlers. 17 The Egg Harbor people believed that too much was decided in Philadelphia and that the actual settlers had not sufficient influence in the affairs of the association. "Equal rights for all shareholders" was the battle cry. Under such pressure the association revised its constitution in a more democratic manner and on May 2, 1860, elected a new board of directors on which the settlers were represented by some of their prominent spokesmen. 18

In the late fifties it looked as if the new settlement really were going to town, or rather to become a town. During the year 1856 the future city area was officially surveyed. In summer 1857 the Governor of New Jersey and a committee of the New Jersey Legislature raised the prestige of Egg Harbor by an official visit. The railroad company again came forward with a little inducement: whoever would build a house within a certain distance of the line, would receive a free railroad ticket for six months and reduced fare for three years. 1858 the first municipal election took place. A citizens’ handbook in German was compiled and published to stimulate the interest in civic affairs. 19 A citizens’ organization, the previously mentioned "Conservative Männerverein," began to make its voice heard in a weekly paper, the Egg Harbor Pilot.

"Pilot" in the name of the newspaper, "harbor" in the name of the city reflect the nautical aspirations which hovered over the history of the city in its first years. According to the original plan the Mullica or Egg Harbor River, which was to form the northern boundary of the city, was to be made navigable for seagoing vessels. Egg Harbor City would then be a commercial city with direct waterways to New York and Philadelphia. On the old city map we can still see various "Landing Channels" along the south bank of the river. One street near the projected docks would be called Antwerp Avenue; perhaps the promoters had visions of a port of debarkation for streams of European immigrants. 20 The river at that time must have been accessible to small seacraft, for we hear that in October 1860 the steamer "Huntress" with 150 passengers traveled from New York to Egg Harbor. At the same time schooners with lumber cargo sailed regularly between Gloucester Landing and New York City.

If Egg Harbor City would really grow into an industrial and commercial center and trading post for agricultural products, then the low freight costs of water transportation would certainly constitute an important factor in its development. However, Egg Harbor never became a harbor. The city never grew big enough to reach the river and the river never was deep enough to be navigable by big seacraft. Soon the railroads monopolized the entire traffic to and from Egg Harbor City. The dream of the big harbor died hard. An editorial opening the fourteenth year of the Pilot (1872) still was couched completely in maritime language. It ended with the vigorous salty stanza:

| Frisch auf Matrosen, die Anker gelichtet, |

| Die Segel gespannt, den Compass gerichtet. 21 |

Where and how they wanted to sail in the sandy soil of the New Jersey woods remained mysterious. Yet, still today the official seal of the city shows a ship with bulging sails, sailing through dramatically choppy waves up into a river. 22

In most German-American newspapers around 1860 there were periodical reports on the growth of the colony. Advertisements in the German papers in Baltimore, Buffalo or Cincinnati made the reader believe that if he invested $500 in Egg Harbor his children and grandchildren would have no worries whatsoever. The pioneers in the New Jersey wilderness were more concerned with the stark realities of 1860 rather than the visionary metropolis and international port which supposedly would spread out there by 1940. The Egg Harbor Pilot reprinted one of these propaganda reports which had appeared in a German newspaper in St. Louis, with a glowing description of a paradise in New Jersey, conveying the impression that most of the ambitious plans for the future had already been materialized. Adds the Pilot wryly: "Every reader will know how truth and fiction are mixed here." 23

The Reverend Georg von Bosse who in the nineties spent several years in Egg Harbor described the beginnings of the town in his autobiography: "Factories, parks, a singer park, a turner park, a botanical garden, a model farm, wide squares for public buildings—everything was provided for in the plans. A scheme of shares and stocks should finance the project. The money actually began to flow, even Germans in the Western states often invested hundreds of dollars in the experiment. Only the people failed to arrive, colonists, settlers, immigrants, those thousands of Germans who were supposed to populate the projected city and bring that German community life of which everybody had dreamed. By and by a few hundred came, and what did they find? Bushes, swamps and swarms of mosquitos. Most of them were utterly discouraged, yet they now were trapped and found themselves to be proprietors of building lots which they had bought sight unseen. The only thing they could do was to keep their chins up and go to work . . . Gradually there grew out of this wilderness not a gigantic city but a charming German town." 24

This particular hope of the founding fathers actually was fulfilled: Egg Harbor became an exclusively German town and remained such for more than half a century. The town developed all the characteristic features which between 1860 and 1910 came into full bloom in the "Little Germanies" of many American cities. Yet, whereas the Germans in Philadelphia, Columbus or Minneapolis always remained a minority within English speaking surroundings, in Egg Harbor City they constituted the town. Anyone who did not speak German was a foreigner here. Anywhere else the Germans as a racial minority showed a certain tendency to noisy self-assertion, occasionally bordering on aggressiveness, mixed with repeated complaints over lack of recognition and appreciation. In Egg Harbor things were more relaxed. Since there was only one element, there could be no tension. Nobody suppressed the immigrants and if they were not appreciated they could not blame anyone but themselves.

The municipal government was organized in 1858. On June 8, 1858 Philip Mathias Wolsieffer was elected the first mayor of Egg Harbor City. 25 On these and the following ballots there was not a single non-German name and so it continued to be during the next fifty years. 26 For more than half a century all business in the City Council was conducted in German. It was only for the convenience of county and state officials that the minutes were kept bilingual. The first entry of these minutes, still preserved in the Municipal Building, shows the date June 18, 1858. On the left page we see the English, on the opposite page the corresponding German text. In this way the Council minutes were recorded until the first World War.

The Gloucester Farm and Town Association was particularly interested in enticing young couples to come to Egg Harbor. In this way the domestic growth of the population would supplement the importation of settlers from outside. Young couples with children would primarily be concerned with the school facilities. Thus the Association provided funds from which the salaries of teachers and the rent of school rooms could be paid. The first teachers of the town were Hermann Trisch and William Frackmann. In the beginning there were only unsatisfactory temporary arrangements: school was held in the so-called Excursion Hall, until finally in 1876 a comfortable schoolhouse was built. With regard to the school question it is interesting to note that the town officers, in spite of their German background, strictly adhered to the common American practice of keeping the public school free of all religious affiliations. A petition, signed by several women, requested that the teacher should conduct classes in religion. The city fathers ordered the clerk "to give notice to the petitioners that the Common Council had no authority to dispose of the teacher beyond school time, and that it was no business of the City Council to meddle with religion." 27

Next to the school the most important institution in most German-American communities was the church or rather the churches. Within the first fifteen years four German churches were organized in the town: The Moravian Brethren, the Catholic St. Nicholas Church, the German Reformed Congregation and the Lutheran Zion Church.

During the very first years of the colony there was no church. A minister of the Reformed Church, Ulrich Gunther, lived in Egg Harbor for a while and in a true Christian spirit of non-discrimination ministered to each and everyone who was in spiritual need. The Egg Harbor people then applied to the Boards of the Lutheran and of the Reformed Churches for regular preachers, but their pleadings produced no action. Upon the advice of the Rev. Gunther they now made an application to the Home Mission Board of the Moravian Church in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. The Board explored the situation and in March 1859 sent the first regular preacher to Egg Harbor, the Rev. Christian Israel who organized a Moravian congregation with sixty-six communicants and sixty-three children. 28 Services were initially held in Excursion Hall (the all-purpose community center) and in the private home of one of the members. In 1860 the congregation decided to erect a church, induced by an offer of the Gloucester Association which promised to donate five lots for a church structure on condition that the building be erected in that same year 1860. The Association seizing upon every chance to enlarge and consolidate the settlement made later similar offers to other congregations. Actually the Moravians beat all the others and dedicated their church building on Palm Sunday, 1861.

At the end of the fifties the German Catholics in Egg Harbor also began to move. Originally they were part of St. Mary Magdalene of Millville, N. J. Old timers pass on the story that a Father Martin Gessner came over, riding on a white horse to tend the shepherdless flock. After the usual trial period of ambulant services in private homes, St. Nicholas Church, still in use today, was erected in 1863-64. 29 At the same time the bishop indicated that he would send a regular priest if the congregation could pay a yearly salary of four hundred dollars. This was answered in the affirmative and the first priest, Father Yunker, was duly installed.

The beginnings of the Reformed as well as of the Lutheran congregations go back to a common start in the year 1859. After the traditional Egg Harbor beginning in Excursion Hall, the Evangelical-Reformed Congregation organized itself in 1862 and affiliated itself with the Philadelphia Classis of the Reformed Church. The Rev. J. P. Pfister served for a brief term, then a colorful personality, the Rev. Anton von Püchelstein took hold of the rudder with a firm hand. Under his guidance the congregation increased to 119 members. He also began the construction of a church building. Notwithstanding such merits, he later figured conspicuously in the annals of the church through his dubious financial dealings and his stubborn (and from his point of view understandable) resistance to produce the accounts. 30 In spite of this and other adversities the congregation lived on and in 1912, when the fiftieth anniversary was celebrated, still gave evidence of its German character.

"In Excursion Hall there are many mansions," one could paraphrase the scripture. True to its supradenominational spirit it also sheltered the first worship of the Lutherans. The Rev. C. A. Fritze from Carlisle, Pa. preached there for the first time on November 20, 1859, and on the same day the Lutherans constituted themselves as a regular congregation, called Evangelisch-Lutherische Zionsgemeinde. A few months later they elected the Rev. Fritze as their regular pastor; a church was built in 1867. The first thirty years of the congregation were a history of schisms, factions, stormy meetings and resignations, of a tug of war between those who wanted to affiliate with the Pennsylvania Synod and those who found the Missouri Synod more inspiring. There were numerous changes in the pastorate and long shepherdless intervals in which some educated layman on Sunday morning read chapters from the Bible. 31 A period of greater stability began in the year 1889 when Zion Church eventually joined the Pennsylvania Synod. In the next decade the pastorate of the Rev. Georg von Bosse contributed much to the reorganization and consolidation of this sorely tried flock. 32

Not the churches or schools, but the singing and gymnastic societies represent the most characteristic features of a true German-American community of the nineteenth century. The trunks of felled trees were still lying around, the streets were still mudholes when in June 1857 the first singing society, Aurora, was founded. 33 As was the case with most societies, it had its period of "storm and stress," but it survived into the twentieth century and for six decades remained the most popular and most respected social organization in town. Founded by a man who stood at the cradle of the two first singing societies in the United States, Philip Mathias Wolsieffer, it soon gained additional prestige when its founder and conductor was elected the first mayor of the town. Well supported by the majority of the citizens, the Aurora interrupted the dullness of every day life by many a concert or theatrical performance. In all such endeavors of community music this German-American generation of 1860, not yet condemned to radio and television, produced an enthusiasm and energy which is probably unparalleled in our time.

We have only scanty knowledge about other societies, yet there were many. We hear about five other organizations with musical ambitions, the Caecilia Männerchor, Germania Liederkranz, Beethoven Verein, Arion Orchester and the Germania Cornet Band, not to mention various church choirs. Two gymnastic societies, the Turnverein Vorwärts and the Germania Turnverein, exerted probably the same attraction here as in other German-American cities. A Plattdeutscher Verein, a Schwaben Verein and a Grütli Verein provided a touch of regional sectionalism, so characteristic of the Germans at home and abroad. We find a Rothmänner Loge and an Odd Fellows Loge, both typical for the roster of organizations in the "Little Germanies" of that time. Unusual was the founding of an Agricultural Society (Landwirtschaftlicher Verein, 1859), with the purpose of disseminating useful seeds and plants and of maintaining a model garden near the town. We know little about this organization. It must have had some prominence since in 1863 a newly founded nationwide German-American Agricultural Society held its first general meeting in Egg Harbor City and decided to establish here the "model farm" of the organization. 34

Nothing unusual for German-American surroundings was an intense interest in amateur theatricals. Two dramatic societies, Dramatischer Club Thalia and Dramatischer Verein Frohsinn, rivaled with one another on the stage. To be sure, the program seldom rose above the entertainment level, yet occasionally the programs showed the best names and titles, such as Mozart’s Zauberflöte, Weber’s Preciosa, Lortzing’s Wildschütz, Schiller’s Räuber, Nestroy’s Till Eulenspiegel, Anzengruber’s Pfarrer von Kirchfeld. More frequently we find the titles of entertaining and melodramatic plays with a broader appeal, such as Schönthan’s Raub der Sabinerinnen, Kotzebue’s Feuerprobe, Charlotte Birch-Pfeiffer’s Goldbauer. There was, of course, also a great deal of fifth grade coarse comedy and ghost drama and we enumerate only a few of these titles which were produced on the Egg Harbor stage: Leonore, die Grabesbraut; Die Glatzköpfe; Der tolle Schneider; Die schlaue Witwe; Ehestands Zwist und Frieden; Einer muss heiraten. Without knowing more than the titles we understand that the editor of the Pilot again and again had to report: "Das Haus war zum Erdrücken voll."

The interest in theatrical performances seems to have been rooted very deeply in the hearts of the Egg Harbor people. When it then happened that this beloved institution was attacked, there resulted quite an uproar. Egg Harbor had no Blue Laws. On Sundays, people could meditate or celebrate, worship or dance, go to church or to the theater as they pleased. This liberality produced on Sundays a considerable influx from surrounding towns where people had to live more in the tradition of the American puritans. The Egg Harbor innkeepers praised this happy constellation, the ministers looked at it askance. In the nineties the theatrical activities in the town received new impetus through the arrival of a professional actor Otto Reuter, who on Sunday evenings drew a number of young people as amateurs into his performances when they were supposed to sing in the church choir. All this prepared a dramatic conflict between the actor Otto Reuter and the pastor Georg von Bosse, who induced the mayor to prohibit theatrical performances on Sundays. The columns of the Pilot reflect the wave of indignation that came in the wake of this unpopular ordinance and for several months a war of "Letters to the Editor" was carried out between the pro-Reuter Pilot and the pro-Bosse Beobachter. 35 The episode which had started on a lofty level, discussing the educational mission of the stage, had an ignominious ending: accusations of immoral conduct, a violent marital quarrel between the actor and his wife in the public street, in which he called her "Satansweib," hasty departure of both with destination Brooklyn, in their wake unpaid debts and open scandals . . this may suffice. It must have been one of those cases where a good cause was represented by a bad man.

All these organizations met in various halls, inns and taverns with names such as Tonhalle, Turnhalle, Rheinhalle, Germania Halle, Schweizer Halle, Rathskeller, Gambrinus Höhe, Gasthaus zum Hirsch, Gasthaus zur Stadt Augsburg, etc., 36 —names which could be matched in Cologne, Stuttgart or Basel.

Still, it is only fair to point out that German-American social life in those decades was more than just folksong and beer drinking. Not everything was Kirmes, Maskenball and Sängerfest, not everything centered around Stein, Handkäs and Sauerkraut. Through many years the Egg Harbor newspapers listed series of lectures of an adult education organization, called Fortbildungsverein. It sponsored talks which were to familiarize the public with the philosophical-scientific outlook of the modern school of thinking, with the works of men such as Feuerbach, Darwin and Haeckel. 37 The Pilot reported regularly about the progress in the fields of the humanities and the natural sciences. In 1869 the paper published a long serialized article on modern pedagogy in the sense of Friedrich Fröbel. 38 As late as 1910 we hear about a "Deutsche Literarische Gesellschaft von Egg Harbor."

The roster of societies does not permit any conclusion as to where the Egg Harbor people stood with regard to the controversial political events in Germany in the middle of the century. The settlement was founded seven years after the unsuccessful German revolution of 1848 which brought so many German refugees to America. However, there are no indications that the Forty-eighters played a conspicuous part in the history of this town. 39 To be sure, there were different shades of opinion. The Aurora minutes of October 4, 1857, mention the purchase of a black-red-golden flag, symbol of the liberal German movement of 1848. By and large, the Forty-eighters seem to have avoided the settlement. They had a greater predilection for big cities or at least some atmosphere of urbanity. Egg Harbor in its first ten years meant hard work in brush and field. When the settlement finally took on an air of civilization, the Forty-eighters had scattered widely and taken root elsewhere. We find in Egg Harbor more men of the old German immigration, the so-called "Grays" (such as Wolsieffer and Schmoele) rather than the "Greens," i.e. the post-revolutionary wave of immigration. In general, the atmosphere seems to have been tolerant. If the singing society had acquired a black-red-golden flag in 1857, they also embraced the new black-white-red of the Bismarck empire in 1871: the Aurora gave a charity performance to help the widows and orphans of the Franco-Prussian War and in January 1871 celebrated the end of the conflict and the founding of the German Reich.

With regard to American politics, the town cannot be given a consistent Republican or Democratic label. Throughout the sixties and seventies the Pilot reported Republican majorities for Egg Harbor. This must have changed at the time of Grover Cleveland, for after the election of 1884 the paper admitted that the Democrats won the entire ticket. The Pilot, a Republican paper, added scornfully that for some years Egg Harbor had been known as "ein Demokratisches Nest." 40 Eight years later the paper again had to report that in Atlantic County, otherwise a Republican stronghold, Egg Harbor City voted for Cleveland 3 to 1. 41 Thereafter the town went into the Republican camp, gave its majority to McKinley and, to the Pilot’s great satisfaction, "repudiated the Bryan farce." 42

No other medium permits one to feel the collective pulse of an immigrant group as clearly as its newspapers. No other immigrant group in the United States has produced a more prolific and more diversified press than the Germans. Needless to say, Egg Harbor had its fair share of German newspapers, indeed there were years (at the end of the century) when the city had four of them at the same time.

The first Egg Harbor paper grew out of the peculiar origin of the town. The Unabhängige Heimstätte was so to speak the house organ of the Gloucester Farm and Town Association, set up as a means of communication between the "mothering" settlement society and the settlers in the bush. It contained the official records, the proceedings and the news of the Association. We know of it only by hearsay; it must have gone out of existence in 1858. By that time the settlers had organized themselves into what they called " Conservativer Männerverein," with the purpose of terminating certain "abuses" of the officials of the Association and of promoting the interest of the settlers. Their press organ became the Egg Harbor Pilot, the newspaper with the longest and most influential history in the town.

The Pilot, which outlived all its competitors, described the reasons for its existence in an anniversary article in 1909. 43 It was founded to counteract the irresponsible activities of the agents of the Association. These men, the Pilot said, had usurped power, they were spendthrifts, negligent in their official duties, they often lured people to Egg Harbor under false pretenses, pictured Egg Harbor as a built-up settlement with paved streets and gas lights at a time when there was nothing but mud, brush and mosquitos. The first issue of the Pilot, edited by Dr. Robert Reimann, came out on December 18, 1858, but the paper was discontinued after thirteen issues, on March 19, 1859. One year later, on March 22, 1860, the paper was reissued, edited now by Hermann Trisch. In the summer of the same year, the "Conservative Männerverein" retired from sponsorship and from then on the newspaper was published independently until its demise in the First World War. Throughout its entire history it was issued as a weekly. 44

In its first year the paper was almost exclusively absorbed with what the Germans call "Kirchturmspolitik," i.e. local affairs in the narrowest sense of the word. In a time when the country was shaken by a Civil War, the Pilot devoted only a few lines to national events. The last issue before the crucial presidential election of 1860 completely ignored the campaign, the first issue after the election dryly reported the result in a few statistical tabulations. 45 Yet, there was in the same issue enough space for a drawn out elegiac contemplation on autumnal beauty, titled "Der Herbst." A headline "Message of the President " does not give the floor to either Buchanan or Lincoln, but turns out to be a message of the president of the Gloucester Farm and Town Association. When in these years the Pilot spoke about the Constitution, it was not the American Constitution but the constitution of the Gloucester Association. Only for the news of Lincoln’s assassination the paper for once stopped being local: the issue of April 22, 1865 appeared with black margins of mourning and devoted its whole first page to the dramatic events in Washington.

This colorless neutralism in domestic politics was abruptly changed in 1868. An editorial announced that from now on the Pilot would plunge into politics. To prove that he meant what he said, the editor then embraced the Republican Party and swallowed its entire platform hook, line and sinker. 46 The election of Ulysses S. Grant was fervently recommended to the people of Egg Harbor. From now on the paper remained consistently Republican for more than thirty years. In 1872, Grant was again presented as "a noble character" 47 and so were all his successors on the Republican presidential tickets until the end of the century, not excluding James Blaine. In those decades the Pilot participated most vividly in each campaign and celebrated jubilantly each Republican victory. If, as it happened in 1884, the people’s choice turned out to be a Democratic candidate, the paper mentioned the outcome in only a few words. Democratic candidates were treated with unmitigated wrath in the editorials. Only in the case of Grover Cleveland did their hostility show signs of restraint: they paid him the compliment that he was better than his party. Once Cleveland was out of the picture and the name of William Jennings Bryan appeared on the Democratic ticket, the Pilot showered the "popocratic candidate" with all the invectives in the book. A big headline after McKinley’s election announced: "The honor of the nation and domestic peace have been saved." 48 The second McKinley campaign was the last one in which the paper identified itself unequivocably with a candidate. Four years later it could not really warm up to Theodore Roosevelt. The editorials spoke cautiously of his "imperialism," of the possibility that such an "impulsive man" might lead the country into unnecessary difficulties—although in the end the paper still recommended the Republican ticket. 49

After the 1904 election the Pilot became as colorless in national politics as it had been in the first decade of its existence. The campaigns of 1908 and 1912 passed without specific recommendations. With regard to the local and state elections the Pilot concluded with an audacious and sweeping gesture that all candidates of all parties for all offices were all "very honorable men." 50 Evidently the struggle for survival had now become more severe. The paper could not afford any more to antagonize that part of the Egg Harbor population which had Democratic leanings.

It is interesting to follow the attitude of the Pilot towards the one man who by most of his contemporaries was considered the symbol of a successful and well integrated German-American immigrant, Carl Schurz. It turns out that the opinions of the paper were completely conditioned by party-line considerations. When Schurz endorsed the Republican candidate, the paper was pro-Schurz. When Schurz stepped out of the party confines, the paper cried "crucify!" In 1872 when Schurz did not support Grant, the Pilot declared that Schurz was "politically dead," that he made himself ridiculous and that he followed only his own selfish interest. "No, we are not proud of Carl Schurz!" 51 The wind blew immediately from a different corner when four years later Schurz campaigned for Rutherford Hayes. The paper now told its readers with great satisfaction that Schurz had come out for the Republican candidate in an "extremely dignified and lofty letter." 52 All this dignity and loftiness did not help the great German-American when in 1884 he refused to go along with James Blaine and instead supported his Democratic opponent Grover Cleveland. The Pilot had no doubts about Schurz’ motivations: personal enmity dating back from the years when Schurz was Secretary of the Interior and Blaine a Senator. This was the reason why now Schurz tried "to slander" the Senator from Maine. "It is sad that this great and eminent Mr. Schurz behaves like a picayune dirty political wire puller, only because he wants to carry out his vengeance." 53 The columns of the paper in these months were full of attacks on Carl Schurz and some were by no means discreet or subtle: "You should be pitied that in your advanced years you have stained yourself with treason to your party." As the colonists had had their Benedict Arnold, the Republican Party now had its Carl Schurz. 54 Again in the campaign of 1900 when Schurz failed to endorse the Republican candidate McKinley, the Pilot spoke of Carl Schurz only with condescension and contempt: "he has become silly, does not know what he talks about or what he wants "—." regretted by his friends, pitied by his admirers, denied by his fellow party members." 55

Six years later Carl Schurz died. The Pilot adhered to the old Roman maxim De mortuis nil nisi bene and devoted its entire front page to a very positive evaluation of the life and achievements of Schurz. 56 "One of the greatest Germans in America . . . patriarchal stature . . . awe inspiring with his never stained shield of honor . . . always fighting for the ideals of his country, of freedom, justice and progress . . . A shining example of civic virtues." There was no trace of criticism. The paper hinted sadly at the numerous disappointments which had beclouded the life of the deceased, but failed to add that the intolerant and dogmatic attitude of the Republican German-American press, such as the Egg Harbor Pilot, had contributed a great deal to the disappointments and disillusions in the career of the German-American patriarch.

It is much more difficult to gauge the attitude of the Pilot towards the events of European politics. It may be said in general that the German-Americans experienced their most liberal era in the two decades between 1850 and 1870. After 1848 many identified themselves with the liberal movement. From 1870 on the lure of the Bismarck empire proved so strong that most German-Americans somewhat forcibly reconciled their liberal past with the not-so-liberal German present. The Pilot, though generally non-political during the sixties, occasionally showed signs of liberal tendencies. It gave fervent praise to Garibaldi, "the noble leader, the symbol of national virtue," and expressed the hope that also the German people some day would find such a "redeemer." 57 There were a few other symptoms of political liberalism when the paper sharply castigated antisemitic excesses in Rumania. 58 The Pilot showed remarkable independence when, unlike most other German-American newspapers, it published an extremely critical report on the political atmosphere in the Bismarck empire at the occasion of Friedrich Hecker’s famous speech in Stuttgart. It reported the address verbatim under the headline "They want to be neither taught nor converted." 59 Hecker criticized severely the political mechanism of the new empire which had been built from the top, not from the grassroots. "Germany is great as a military power, yet small as a nation, much smaller than in 1848 when it not only wanted to be united, but also wanted to be free." Germany in 1873 meant police regime, lack of social justice and freedom, servility of the officials and brutality of the military (said Hecker), and all this would prevent the German people from using their unity for the higher purpose of civil liberties. Since the Pilot printed Hecker’s widely noticed evaluation of the German Reich without any commentary, we may assume that the editors themselves were not entirely in agreement with the political course in Germany.

However, during the eighties and nineties we notice an increasing interest in German affairs which then were reported without any fundamental criticism. When Bismarck died, articles on his career, born out of great admiration, covered the entire front and rear pages of the issue. For the Pilot Bismarck was "the man of the century." 60

After the turn of the century the space devoted to European politics decreased rapidly. In matters of domestic as well as international politics the paper became more and more colorless. The outbreak of the World War in 1914 was not even noticed. Soon after, however, we begin to discern a certain political drift which the Pilot in these years shared with many other German-American papers: a strongly anti-British attitude and the wish to keep America neutral in the European conflict. The paper had no individual political profile any more, it reprinted mostly pro-German articles from other German-American newspapers. This line of argument which more and more fell out of step with American public opinion may have hastened the end of the paper which closed its office some time in 1917. 61

The literary contributions in the columns of the Pilot hardly ever rose above the level of a provincial German paper. We find some novels and stories by Paul Heyse, Karl Gutzkow, Clara Viebig, Friedrich Spielhagen, Fedor von Zobeltitz, Peter Rosegger, F. W. Hackländer, Alexander Dumas and Otto Ruppius, poems by Uhland and Freiligrath, a series of geographical articles by Alexander von Humboldt. This may suffice to indicate the modest literary ambitions of the editors.

Compared with the Pilot all other German papers in Egg Harbor played second fiddle. In most cases no copies are preserved. As so frequently in German-American newspaper history we know about some papers only through indirect hints in other papers. Thus we learn that in 1858 there was a Beobachter am Egg Harbor River. 62 Again through an indirect source we know of the demise of the Aurora which passed away because it could not collect its outstanding assets. 63

Shortly after the Civil War the town had a second German paper Der Zeitgeist which throughout more than three decades was the strongest rival of the Pilot. Under the editorship of Moritz Stutzbach it began its publication on April 6, 1867. Politically it was listed as independent, but it must have had some leanings towards the Democratic Party. 64 In 1887 the editorship passed into the hands of George F. Breder who later changed the name of the paper to Deutscher Herold. Breder became a good friend of the Rev. Georg von Bosse who frequently contributed religious articles and travel descriptions. Von Bosse noted in his autobiography that the Zeitgeist-Herold was the only Egg Harbor paper which had a decidedly sympathetic attitude towards the Christian churches, whereas the others were either indifferent or hostile. 65

In 1879 another paper made its appearance, Der Beobachter, edited by Wilhelm Müller. 66 From 1895 until 1900 Robert Weiler published a weekly Der Fortschritt which then was discontinued on account of illness of the editor. 67 Just as a matter of curiosity we mention that during the carnival season in the last two decades of the century there appeared irregularly scattered issues of an Egg Harbor Carneval Zeitung.

Perhaps the most striking manifestation of the German character of Egg Harbor in its infancy is the street map of the planned city. It was drawn up in the late fifties when the founding fathers still had hopes for a metropolis that would stretch seven miles north of the Camden-Atlantic Railroad. We still have this first map which shows the following names for the streets in the West-East direction: Agassiz, Arago, Beethoven, Burger, Campe, Claudius, Diesterweg, Dürer, Egmont, Esslair, Fichte, Follen, Goethe, Gutenberg, Herschel, Humboldt, Irving, Itzstein, Kant, Kepler, Lessing, Liebig, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Naegeli, Neander, Oken, Opitz, Pestalozzi, Pindar, Quantz, Quinet, Rink, Rotteck, Schelling, Schiller, Thalberg, Tell, Uhland, Umbreit, Vogler, Voss, Welker, Wieland, Xenophon, Xylander, Yorick, Ypsilanti, Zelter, Zschokke. This list reflects most impressively the mentality of the people who were the godfathers of the city. A good number of the names honored great men of German letters: Goethe, Schiller, Lessing, Wieland, Claudius, Burger, Uhland, Voss, Opitz, Zschokke. Twice we find the heroes of plays by Goethe and Schiller: Egmont and Tell. German composers appear, such as Beethoven, Mozart and Mendelssohn. Some names taken from the history of German civilization need no further explanation, such as the painter Dürer, the explorer Humboldt, the printer Gutenberg, the educator Pestalozzi, the chemist Justus von Liebig, the philosophers Kant, Fichte and Schelling. Some of these names are still known to an educated German today, but they mean nothing any more to the man on the street, even if he lives on Diesterweg Street. Some of these streetnames are perplexing even to a polyhistor, and we admit that we had to dig deep into encyclopedias of this and the preceding centuries to find explanations for some of the names. Many of these scholars, poets, artists and statesmen never had a street named for themselves in any German city and most of them (like Wilhelm Xylander for instance, a scholar of Roman literature in the sixteenth century) never dreamed that they would have their streets along the Mullica River in the New Jersey backwoods.

We enumerated the street names not because we wanted to give a brief index of Western civilization, but because the names permit us to feel the intellectual pulse of the group that organized Egg Harbor City. We notice the high educational level of these men, their obvious interest in literature, music, philosophy, natural science and the political tradition of nineteenth century German liberalism.

The names of the avenues running from South to North are likewise indicative of the spirit that promoted the Egg Harbor project. They all are named for cities. Among American cities those were especially honored which were known for their large German sector: Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Baltimore, St. Louis, New York, Buffalo and others. A great German-American influx was expected from these places. The avenues named for world sea ports, such as Hamburg, Bremen, London, Liverpool, Antwerp, Norfolk gave premature honor to prospective partners in world trade.

Most of these streets and avenues remained just names on a gigantic oversized map. This old map of Egg Harbor City is an eloquent monument to unfulfilled dreams, a barometer of ‘the maritime aspirations as well as the intellectual climate of the group behind the Egg Harbor experiment. When you drive a few miles north of the city, you will in the midst of the woods, marking nothing but an idyllic forest path, encounter some of these signs, announcing that you now are crossing Uhland Street or Pestalozzi Street, crossings considerably more peaceful than the corner of Lexington Avenue and 86th Street.

The first settlers who came to Egg Harbor in 1855 were probably small farmers. Soon after the Civil War various branches of small industry began to develop, the most important: tailor shops, the wine industry, a brick yard, a cut glass factory, a carriage factory, a lumber yard, a brewery, a cigar factory. 68 "Fifty to sixty years ago," Mr. Ernest Beyer, an Egg Harbor old timer, told us, "Egg Harbor had nothing but tailor shops and the wine industry. There were perhaps 25 or 30 tailor shops located in the town each employing from two or three upward. An establishment of a dozen was considered good; a few even had 20 or 25 workers. The working day was about ten hours. Many housewives had coats delivered to their homes for a slight finishing touch, receiving a small amount for their labor. It was an industry that meant much to this city of very industrious people." A bank was founded, two Building and Loan Associations were organized, several hotels were built to accommodate out of town businessmen. The town never became rich, but still fairly prosperous.

With tailor shops, cigar factories and other industrial enterprises the town did not differ from hundreds of similar New Jersey settlements. The one feature through which Egg Harbor rose to its own and unmistakable identity was the wine industry. From the first years to the present time this gave its special imprint to the town.

It would be interesting to follow up the numerous (and mostly unsuccessful) attempts which German immigrants have undertaken to make wine an acceptable beverage in this country. During the first half of the nineteenth century John Gruber in his Hagerstown Almanac again and again urged his Maryland German farmers to switch from "the stinking whisky" to "the magnificent wine which keeps men healthy, strong and happy." The German settlement of Hermann, Missouri soon after its founding in 1830 became known for its wine raising and established the tradition of an annual wine festival. Kaspar Schraidt, a Forty-eighter, made a name for himself as viticulturist and introduced the cultivation of grapes on the island of Put-in-Bay in Ohio. Herrmann Schuricht, living at the end of the nineteenth century near Charlottesville, Virginia experimented with grape cultivation and made propaganda for it extensively in a German weekly Der Süden. These are only a few examples among many. The Germans of Egg Harbor tried more patiently and more insistently than all others to plant the grape into American soil and the love for wine into American hearts.

Alexander Schem, when he entered a few lines about Egg Harbor in his German-American Encyclopedia, 69 mentioned as a special attraction that the town had "herrliches Trinkwasser—magnificent drinking water." The speedy erection of a brewery one year after the founding of the town indicates that the Germans in Egg Harbor lived not only on "Trinkwasser," no matter how good. At the same time, in 1856, the first experiments with grapes were carried out. The pioneers in the wine industry were Ph. M. Wild, F. J. Rödiger and August Heil. Climate and soil seemed to be favorable. In the beginning the wine was made for home consumption. Soon they began to sell it outside of town and state, and in the decades after 1870 the wine industry became the most important source of income for the people. At the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia (1876) and at a Wine Exhibition in Paris (1878) the Egg Harbor wines won prizes. The Camden and Atlantic Railroad, the patron saint of Egg Harbor, in 1879 invited a group of prominent men from New York and Philadelphia to a big wine sampling party in town. As guests of the railroad they inspected "the comparatively new and profitable industry of the grape culture and wine making . . . There are between 700 and 800 acres of vineyards now planted in the Egg Harbor district and growing finely." 70 The New Brunswick paper which reported the sampling excursion saw in the production of wine "the greatest agent that could be brought forward in this country in favor of temperance," and it hoped that God would "speed the day when we will be able to produce enough wine in this country to keep young men out of the gin shop and rum mills."

Anyone who peruses the old files of the Pilot will see how prominently the cultivation of wine figured in the minds of the Egg Harbor people. Again and again the paper published articles on grapes, many written by Ph. M. Wild. 71 The wine industry soon became a special drawing point for out of town visitors. Many a German-American excursion was organized in Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington or New York to taste the products of the Egg Harbor vineyards. Particularly around the Fourth of July and again in autumn, the town organized indefatigably a string of festivals: Weinfest, Winzerfest, Weinlesefest, Oktoberfest and other pretexts for fluid hilarity German style.

We mentioned before that no Blue Laws restricted this general buoyancy of the town. Not everybody was happy about it. A reporter from the South Jersey Republican had visited one of the Egg Harbor fairs and returned shocked, speaking of "Trunkenbolde" and "schweinisch besoffene Menge." He was duly castigated in the local German paper for his adverse criticism, with dark allusions to the effect that the man probably was an anti-immigrant Knownothing. 72 Still, a whole generation later, Pastor Braun of the Baptist Church in Egg Harbor wrote in an article: "Although I am with heart and soul a temperance man, I do not notice the same among the members of my congregation, since it consists mostly of Germans who like their drinking too much." 73

It seems that in the first decades the grape raising was the only really successful venture in town. Most other agricultural, industrial and commercial undertakings had a slow start. A great deal of the financial backing, to which out of town stockholders had subscribed, remained on paper only. In 1857 the great world economic crisis shattered a good many hopes of the Egg Harbor sponsors. 74 The Civil War again retarded the growth of the settlement. Many young men joined the army. A company, organized by a Capt. J. J. Fritschby, fought on the Union side with great bravery. 75 Needless to say, the absence of these young men was painfully felt in the colonization chores of the town.

Thus the population grew slowly until the end of the Civil War. Then, however, there was a rapid increase. In fact, the decade before 1870 as a whole saw the proportionately greatest growth of the Egg Harbor population: it almost doubled. In 1868 things looked so hopeful that Veronika Spontowicz, a German midwife, decided to move from Philadelphia to Egg Harbor, where she recommended herself through advertisements running in the Pilot as "geprüfte deutsche Hebamme."

After 1880 the curve of population rose slowly, never again as steeply as in the years before 1870. Here are the official census figures for Egg Harbor City throughout its entire history:

| 1860 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 789 | 1910 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 2,181 | |

| 1870 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1,311 | 1920 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 2,622 | |

| 1880 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1,232 | 1930 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 3,478 | |

| 1890 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1,439 | 1940 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 3,589 | |

| 1900 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 1,808 | 1950 | . . . . . . . . . . . . | 3,838 |

These figures show unmistakably that the original sponsors and settlers of the town had to give up their dream that Egg Harbor would become a big city. They likewise had to abandon the fundamental idea of the whole enterprise, the reason for its existence: that Egg Harbor was and would remain an exclusively German city.

It is possible to determine almost to the day, when the inhabitants of Egg Harbor decided to let the draw bridges down from the gates of their German dream castle and to step into the realities of American life. The newspaper Pilot, which here as so often revealed the pulse of the population, published an editorial on June 20, 1868 which opened a new chapter in the history of the paper as well as of the town. "Only a few among us still cling to the idea of a purely German settlement. More and more we have learned in the last years that such a restriction within self-imposed limitations would constitute an impediment which makes progress impossible. . . . . We shall rather be American citizens than inhabitants of a German settlement in America." The editorial also pointed out that the tensions between nativistic elements and immigrants had been mitigated and that the idea of complete seclusion was not justified any more. The immediate consequences for the newspaper in this moment were: to give up its political indifference and take part in the next presidential campaign. Apparently in the field of domestic politics the peculiar dilemma of the town had become most pressing: they could not vote German, they had to decide between Republican and Democratic candidates for state and national representation.

Egg Harbor City was not an island. Any non-German speaking person who wanted to live there could do so. He would be somewhat isolated, but no law prevented him from taking a job here or opening a store. He would probably do little business if he did not learn German quickly. Towards the end of the century a few colored families moved into town and they soon talked German, in fact, their children spoke it as fluently and free of accent as if they had grown up in Kassel or Kaiserslautern. Another nationality arrived in greater numbers, the Italians. Some were attracted by the wine and grape industry with which they had some familiarity from their Italian origins. Some of them were skilled tailors and found employment in the tailor shops. Some were imported as cheap laborers by the railroad companies. 76 Here was another segment of population with which the Egg Harbor aborigines would have to come to terms. They could not be linguistically annihilated like a dozen negroes. They could likewise not coexist, one part speaking German, the other Italian. Sooner or later they all had to meet on a common platform, as American citizens speaking the language of the country.

There are a number of indications that Egg Harbor towards the end of the century became a bi-lingual town. In 1892 a theatrical troupe from out of town performed for several days, producing English plays. 77 The commencement program of the Egg Harbor school in 1906 clearly shows the two-track character of the language situation: the students performed in German scenes from Schiller’s Wilhelm Tell and in English scenes from Shakespeare’s As you like it. Ever since the sixties a few English newspapers were published in Egg Harbor. For many years they did not prosper too well, they changed hands, moved away, were sold, combined or discontinued, yet, they were not so entirely without support that they would die completely. The names of most of these English papers (Atlantic Democrat, Atlantic Beacon, Atlantic Journal, Atlantic Star Gazette) indicate that they addressed themselves more to the people of Atlantic County than to the population of Egg Harbor City, yet, around 1900, they must have met with increasing response in the town itself. 78

The various church records likewise reveal the transition from a German to an American town which took place after 1900. The Catholic St. Nicholas congregation was the first to give up German as the language of the church records. From 1859 to 1866 they were in German, from 1866 to 1877 bilingual, after 1877 exclusively English. The first sizable influx of non-German speaking people were the Italians, all Catholics. This explains why the Catholic church was by far the first to move out of the German confines.

For the Moravian Church the transition period came considerably later. Its bi-lingual period is the time from 1895 to 1898. Before those years the records were in German, afterwards in English. The Reformed Church held out longer: exclusively German until 1914; bi-lingual 1914-1920; entirely English after 1920. The greatest tenacity was displayed by the Lutheran Church which clung to German in its records until 1932 and then, omitting the usual bi-lingual transition period, changed to English. 79

In 1893 a new church was founded in Egg Harbor City, the German Baptist Church. Starting at a time when German life in town was already declining, this church never flourished. It went through protracted stages of dissolution and was finally disbanded in 1934. Much more successful was the Congregational Church. Organized in 1903 as an English church, when there was increasing need for some church service in English, the Emmanuel Congregational Church was English in the language of the records, the sermons and the social life from the beginning to the present.

What the records of the originally German churches and the organizing of English churches indicated in an unofficial way found its official confirmation in the Municipal Building on April 25, 1916. On that day the deliberations of the City Council for the last time were recorded in English and German. From then on the books were kept in English.

The fiftieth anniversary of the city in September 1905 was the last great community celebration which reflected the German character of the town. Great gatherings and public parades marked the day. A little book was published which recorded the outstanding events in the history of Egg Harbor and the main accomplishments of its citizens. 80 The German-American press all over the country took due cognizance of the birthday and still referred to Egg Harbor as "the most German town in the country." 81 The German paper in Buffalo summed up its impressions: "Undiluted as in few other communities of the country, Egg Harbor has preserved its German spirit and its German language." Yet, retrospectively it seems to us symbolic that the main day of the festival was marred by a melancholic rain.

The difficult years of the first World War only accelerated a development which would have taken place also without the anti-sauerkraut hysteria of the year 1917. The psychological pressure of these years helped to de-emphasize the German components in the texture of the town. Some of the people even gave up the most conspicuous sign of their German heritage, their names. Some of the Morgenwecks (one of the oldest German families in town) changed to Morgan. The percentage of the German element decreased, the Italian element grew. The last census (1950) showed that among 326 foreign born people in town 106 were from Italy and exactly the same number from Germany and Austria. In the telephone directory there is still a great predominance of Teutonic names: Bleibdrey, Butterhof, Einsiedel, Geissenhoffer, Haberstroh, Krauthause, Morgenweck, Obergfell, and assorted Schmidts. Yet, there is also a considerable sprinkling of the clans of Barbetto, Caroccio, Dessicini, Napolitano and Portaluppi.

After the First World War Egg Harbor, for many decades the most German community in the country, became an American town, on the surface hardly different from most other towns in the state. Talk to the people and you discover that they are still keenly aware of the German past and of the peculiar history of their town. Yet it is already so remote that it looks to them like the Golden Age. On a cold winter evening they will tell their unbelieving grandchildren with a nostalgic sigh: "Those good old days, when one could buy a big steak dinner for 35 cents, when nobody paid income tax and when German was spoken on every street."

The Seal of the City

Adopted in 1858

(see note 22)

NOTES

1 According to local tradition the first Dutch settlers entered upon the scenery in spring when gulls and other birds laid eggs in great quantities. Impressed by the sight of the countless eggs they named the place "Eyren Haven," Dutch for Egg Harbor. Alfred M. Heston, South Jersey, A History 1664- 1924 (New York, Chicago, 1924), II, 727.

2 For further details on the ups and downs of the Camden and Atlantic Railroad cf. Heston, South Jersey, II, 719 f.

3 William Schmoele was well known among the Germans in Philadelphia. He was born in Westphalia and studied at the University of Marburg. After his arrival in the United States he became instrumental in the establishment and expansion of some German-American newspapers (Susquehanna Democrat, Pennsylvania Staats-Gazette) and after 1835 made a name for himself as a physician in Philadelphia. He was very active in German-American affairs and helped to organize several building and loan Associations. The Egg Harbor project was very much in line with his interest in cooperative ventures. Georg von Bosse, Das deutsche Element in den Vereinigten Staaten (New York, 1908), 116 f.— Deutsch-amerikanische Geschichtsblatter, X (Chicago, 1910), 141, 144.

4 Heston, South Jersey, II, 745 f. This whole area was generally known as Gloucester Furnace Tract. An iron foundry and furnace had been operated here for many decades.—The minutes of the stockholders meetings of the Gloucester Farm and Town Association are still preserved in the Municipal Building in Egg Harbor City. The first entry is dated November 24, 1854, the last January 5, 1869.

5 In the Municipal Building of Egg Harbor City there is still a little expository pamphlet describing this first monumental plan, Vollständiger Plan der festbegründeten, soliden und volksthümlichen Gloucester Land-und Stadt-Gesellschaft zur Anlegung zweier Städte und 1500 Landgüter in der Nähe Philadelphias, (Philadelphia, Gedruckt bei King und Baird, 1855), 29 pp.

6 New Jersey Session Laws, 1858, Chapter 152.

7 Advertisement in the Baltimore Correspondent, February 3, 1858. Cf. also George F. Breder, (Egg Harbor City, Its Past and Present, Golden Jubilee 1855-1905, (Egg Harbor City, 1905), 13. The various sources of information about the conditions of settlement are not always in accord. They probably underwent some changes within the first fifteen years.—Die neue deutsche Heimath der Gloucester Landgut-und Stadt-Gesellschaft, (Egg Harbor City, 1858, 16 pp. Only copy in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania).

8 Quoted in Breder, Egg Harbor, 13.

9 Breder, Egg Harbor, 15.

10 Correspondent, February 3, 1858.

11 Egg Harbor Pilot, August 18, 1860. We found running advertisements for Egg Harbor in both Baltimore German papers Correspondent and Wecker as well as in the Washington daily Tägliche Metropole. We may well assume that similar notices appeared in most German-American papers around 1860.

12 Correspondent, January 2, 1858.

13 Ibid.

14 Laurence F. Schmeckebier, History of the Knownothing Party in Maryland, (Baltimore, 1899).

15 The advertisement was signed by Jacob Schmidt, Baltimore agent for Egg Harbor. It was published in the Wecker, October 25, 26, 27, 1858. We found other allusions to the Knownothing conditions in various other advertisements, such as the Correspondent of May 6, 1858 in which Egg Harbor was praised as a rejuvenated free German fatherland, developing the German character in purity and perfection, undisturbed by depraved sons of American freedom, observed with love and admiration by the educated citizens of the country."

16 Correspondent, September 30, 1880. This was an error which was immediately corrected by the Egg Harbor Pilot. The Germans of Philadelphia were the godfathers of the New Jersey town.

17 Actually a considerable sum of money had been spent before 1860. The Pilot of June 23, 1861 gave a rough account for the years 1854-1860. Income $440,500; expenses $405,900.

18 Pilot, May 10, 1860. John F. Hall, The Daily Union History of Atlantic City and County, (Atlantic City, N. J., 1900), 115. Even this arrangement did not last too long. In the years after the Civil War it became clear that Egg Harbor never would fulfill the ambitious plans of the original founders. On January 5, 1869, the association, after having gathered all the liabilities, was dissolved. It was immediately followed by a successor organization, the "Egg Harbor Homestead and Vineyard Company."

19 Der Rechtsfreund, Eine Sammlung besonderer Gesetze und Rechtsbräuche des Staates New Jersey nebst den Municipal Gesetzen von Egg Harbor City, (herausgegeben von Louis Bullinger, Egg Harbor City, 1859), 71 pp. Copy in Municipal Building.

20 In the Municipal Building there is a little pamphlet Plan zur Ausführung des Hafenbaues im Flussdistrikt von Egg Harbor City . . . und Gründung einer Dampfschifflinie zwischen Egg Harbor City und New York, (Egg Harbor City, November 1859, Gedruckt bei Louis Bullinger), 16 pp.

21 Pilot, March 30, 1872.

22 This seal which was adopted in 1858 captures symbolically all the commercial and maritime aspirations, the youthful optimism and the sentimental attachment of the colony: the vessel on the river, a rising sun in the background and a broad oaktree in the foreground. Among the Germans the oak has always been considered their" tree, a symbol for German sturdiness, steadfastness and fortitude.

23 Pilot, May 4, 1860. The embellished reports of the St. Louis paper mentioned an Egg Harbor population of 4,000. The municipal election of the preceding year showed that a total of 139 votes had been cast.

24 Georg von Bosse, Ein Kampf um Glauben und Volkstum, (Stuttgart, 1920), 48.

25 Wolsieffer was born in Winweiler, Rhenish Palatinate in 1808. He emigrated to the United States in 1833, was for a while a music teacher in New Haven, Conn. and Philadelphia, spent a few years in Baltimore where he was conductor of the first singing society, later became secretary of the Gloucester Association. He came to Egg Harbor as one of the first settlers and planted a vineyard. In 1866-67 he was a member of the New Jersey Legislature. Later he left the town and spent the rest of his days in Philadelphia. H. A. Rattermann, Gesammelte Werke, (Cincinnati, 1911), XII, 431-434. Bosse, Kampf, 116 f. Rattermann, Anfänge und Entwicklung der Musik und des Gesanges in den Vereinigten Staaten," Deutsch-amerikanische Geschichtsblätter, XII (1912), 340-342.

26 The names of the mayors during the first half century: P. M. Wolsieffer, Josef Czeike, Moritz Stutzbach, Frank Bierwirth, Louis Ertell, William Darmstadt, Daniel Hax, William H. Bolte, George Müller, Louis Kühnle, Moritz Rohrberg, Theophylus H. Boysen, John Schwinghammer, Frederick Schuchhardt, William Mischlich, Louis Garnich.

27 City Council Minutes, May 25, 1859.

28 Hugh E. Kemper, Directory and Handbook of the Moravian Congregation of Egg Harbor City, N.J., (1934), 12 ff. List of pastors until the end of the century on p. 15.

29 The building project started as early as 1858. In the archives of St. Nicholas there is still a pamphlet Anrede der katholischen Gemeinde in Egg Harbor City, N. J. an ihre Freunde und katholische Glaubensbrüder, denen dieses zur Hand kommen mag, in Beziehung auf den Bau einer katholischen Kirche und anderer religiösen Anstalten in Egg Harbor City, (Philadelphia, 1858). The early church records, here as in the other churches, were kept in German. Those of St. Nicholas Church are now preserved in the Chancery Office, 721 Cooper Street, Camden, N. J.

30 For further details see H. J. F. Gramm, Souvenir Programm der deutschen Evangelisch - Reformierten Gemeinde in Egg Harbor City, (1912). Ministers after A. von Püchelstein were H. Losch, Pastor Dechant, Jakob Dahlmann, M. Frankel, John Bachmann, Adam Böley, Carl Cast. From 1882-1902 the organization was served by the ministers of Glassboro, N. J. and Folsom, N. J. Thereafter a gradual reorganization took place.

31 Georg von Bosse, Festbüchlein zum 25-jährigen Jubiläum der deutsch evangelisch-lutherischen Zionskirche in Egg Harbor City, (1892). Until the end of the century the congregation was served by the following ministers: C. A. Fritze; E. F. Richter; Chr. G. Hiller; Pastor Frank; Pastor Vollquartz; Pastor Causse; H. W. Bähr; H. Rippe; Georg von Bosse.

32 The Rev. Georg von Bosse was born in Helmstedt, Germany in 1862, emigrated to the United States in 1889 and after a few years as assistant minister in Philadelphia served as pastor of the Lutheran Church in Egg Harbor from 1891-1897. Thereafter he was minister in Harrisburg, Pa., Buffalo and Liverpool, N. Y., until in 1905 he accepted the pastorate of St. Paul’s Church in Philadelphia which he held until his retirement in 1930. He also became known as an author of historical writings. He died in Rahns, Pa. in 1943. An account of his life until 1920 is to be found in his autobiography Ein Kampf um Glauben und Volkstum (1920). Cf. also New Yorker Staatszeitung und Herold, April 29, 1943.

33 Material gathered from Festschrift zum 50-jährigen Jubiläum des Gesangvereins Aurora (1907). The pamphlet was compiled from the minutes which in 1907 were still available. It covers the history of the society year by year; in many instances it is the only source for the history of other Egg Harbor societies.

34 The Gloucester Farm and Town Association donated the land for the farm under very favorable terms. The members raised $4,000 for the farm and even entertained ambitious plans for a big agricultural institute in Egg Harbor. Information was gathered from a pamphlet Rede von Andrew Lutz, Präsident des landwirtschaftlichen Central-Vereins von Nord-Amerika, gehalten bei der ersten General. Versammlung in Egg Harbor City, (New York, 1863).

35 Pilot, June 7, 21, August 18, 25, 1894. Bosse, Kampf, 62-65.

36 Names gathered from advertisements in the Egg Harbor Pilot.

37 Pilot, July 17, October 23, 1880.

38 The author was a resident of Egg Harbor City, Dr. Emil A. Damm, who also recommended himself in the advertising section of the paper as a tutor in Greek, Latin, French and English.

39 In these same years the people of Northern New Jersey saw the beginnings of a German Settlement which was founded in the tradition of the Forty-eighters. This was the town of Carlstadt, built on a ridge between the Hackensack and the Passaic Valleys. The land had been bought cooperatively by liberal German refugees and freethinkers. Named for Dr. Carl Klein, the leader of the group, this settlement was (as the Baltimore Wecker of October 5, 1858 expressed it) based on " the principles of a social republic." To our knowledge, the history of this interesting colony has never been told.

40 Pilot, November 10, 1860; November 7, 1868; November 7, 1874; November 8, 11, 1884. After the election of 1884 three hundred citizens organized a torch parade to celebrate Cleveland s victory.

41 Pilot, November 12, 1892.

42 Pilot, November 7, 1896; November 10, 1900.

43 Pilot, March 6. 1909.

44 Until now practically nothing had been known about the Egg Harbor Pilot except the name. The Union List of Newspapers does not list a single copy as extant. There is a brief mention in two statistical compilations, New Jersey Newspapers in 1874 " in Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society, New Series, XV (1030), 262, and Die deutsche Presse in den Vereinigten Staaten " in Der Deutsche Pionier, VIII (1876), 294. We were extremely fortunate in locating an almost complete file of the Pilot from 1860 to 1915. The first year is in the possession of Mr. George W. Otto of Egg Harbor City, who has the entire second volume from March 22, 1860 to April 6, 1861. Most of the remainder, from 1862 to 1915, was until recently in the hands of Mr. A. H. Kroekel of Philadelphia, a son of the last owner and editor of the paper. Mr. Kroekel has now deposited this entire file in the Rutgers University Library.

Two anniversary articles of the Pilot (March 12, 1904 and March 6, 1909) clarify the history of frequently shifting ownerships. In the following we list the names of the owners. Often (not always) owner and editor were identical: 1860-1868, Hugo Maas; 1868-1869, A. Stephany and Franz Scheu; 1869-1871, Franz Scheu; 1871, Louis Bullinger, A. C. Morgenweck; 1871-1879, A. C. Morgenweck and Hugo Maas; 1877-1881, Hugo Maas and Charles Kroekel; 1881-1904, Hugo Maas; 1904-1915, Charles Kroekel. Most of these men lived in Egg Harbor for the greater part of their lives. Franz Scheu’s name later figured prominently in the history of the German press in Delaware as editor of the Delaware Pionier and the Wilmington Freie Presse.

45 The local result for Egg Harbor was: 85 votes Republican, 53 Democratic.

46 Pilot, June 13 and 20, 1868.

47 Pilot, June 15, 1872.

48 Pilot, November 7, 1896.

49 Pilot, November 5, 1904.

50 Pilot, November 2, 1912.

51 Pilot, June 15, November 2, 1872.

52 Pilot, August 5, 1876.

53 Pilot, August 23, 1884.

54 Pilot, August 30, 1884.

55 Pilot, September 29, October 20, 1900.

56 Pilot, May 19, 1906.

57 Pilot, June 14, 28, 1860.

58 Pilot, March 30, 1872; also March 4,1882.